Journey of Two Cenotaphs

A cenotaph is a tombstone that has been relocated and no longer rests in place on the original burial site. The Strafford Historical Society received and removed the last two of its artifacts, two gravestones, stored at the Brick Store on February 16, 2024.

Scott Knorlein and Dave Kyner seem to be enjoying themselves as they wrestle the Pennock family cenotaph out of the breezeway at the Brick Store

As artifacts, they are not the easiest to move, store or situate. Eventually, when the Masonic Hall is renovated and landscaped, they will be placed more permanently there. In the meantime, they are being stored in the barn of Dave and Anne Kyner. Our thanks to them for looking after these important pieces of Strafford’s history.

The Pennock family tombstone

being moved at the Brick Store.

A more legible facsimile of this old tombstone is in the photo below. A modern replacement tombstone now stands in Old City Cemetery. It replaced the Pennock family tombstone, a heavy slab of slate, weathered by after many decades spent in the Old City Cemetery, its chiseled script almost indecipherable.

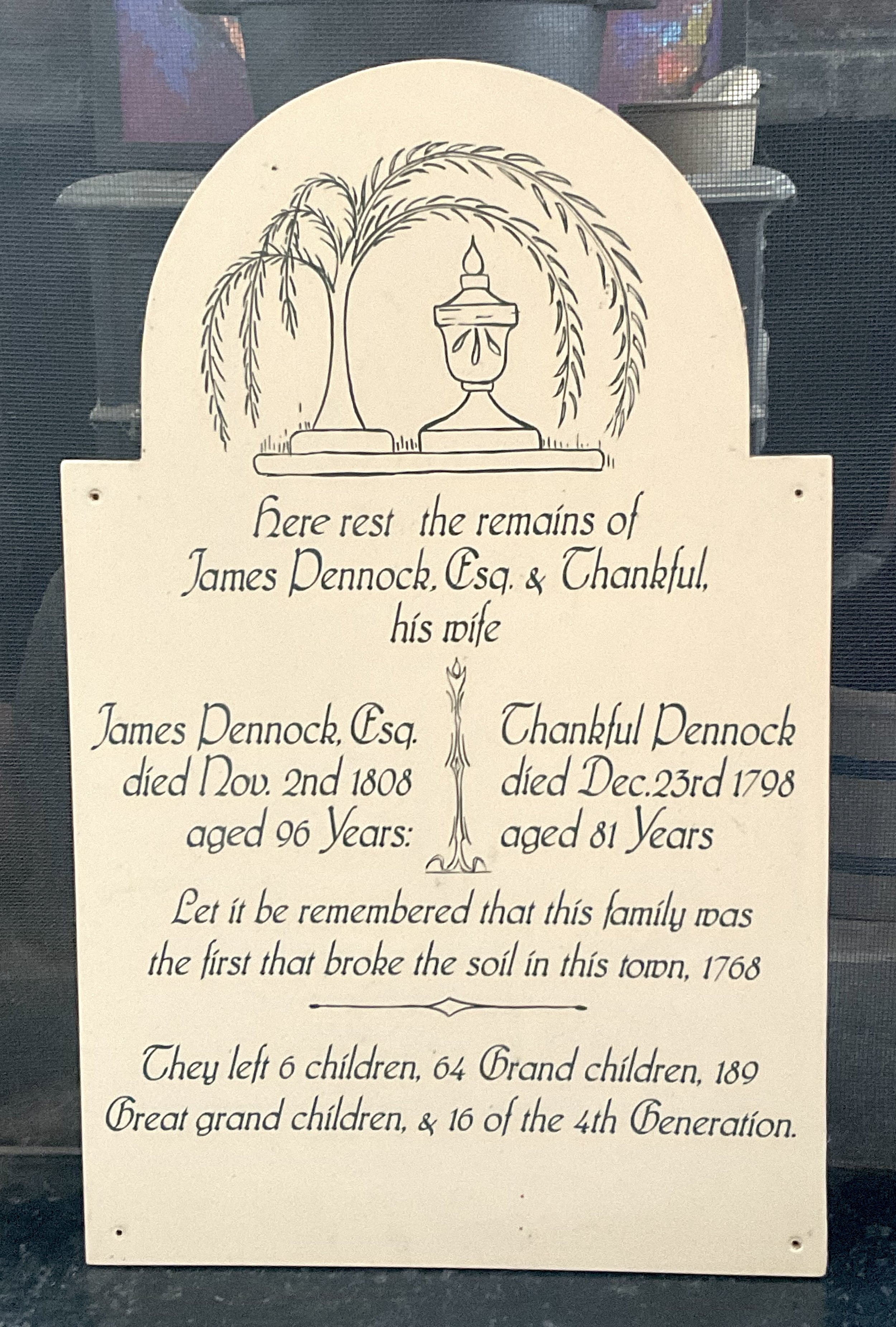

A modern, more legible facsimile of the Pennock family tombstone now stands in Old City Cemetery.

There is something almost elegiac about the Pennock cenotaph’s dedication. The Pennocks were certainly among the first to settle in Strafford and, judging by the epitaph, seemed to have lived long and productive lives with many descendants. James, in fact, served many years as a Justice of the Peace, a Judge and a Magistrate :

‘Here rest the remains of James Pennock, Esq. & Thankful Pennock, his wife. James Pennock, died Nov. 2nd, 1808, aged 96 years: and Thankful Pennock, Esq., died Dec. 23rd, 1798, aged 81 years. Let it be remembered that this family was the first that broke the soil in this town, 1768. They left 6 children, 64 grandchildren, 188 great grandchildren, & 16 of the Fourth generation.’

There is, however, more to their story, including the fact, according to the Early History of Strafford, Vermont, that the number of their children was actually eleven and that eight of their nine sons, at least initially, joined the British side in the Revolutionary War. Three of them were to die at the Battle of Saratoga. The Revolutionary War created bitter divisions in Strafford and presumably also within the Pennock family, because although two of the remaining Pennock sons returned to Strafford, joined the Patriot cause and then served in the local militia, three other sons spent the remainder of their lives in Canada.

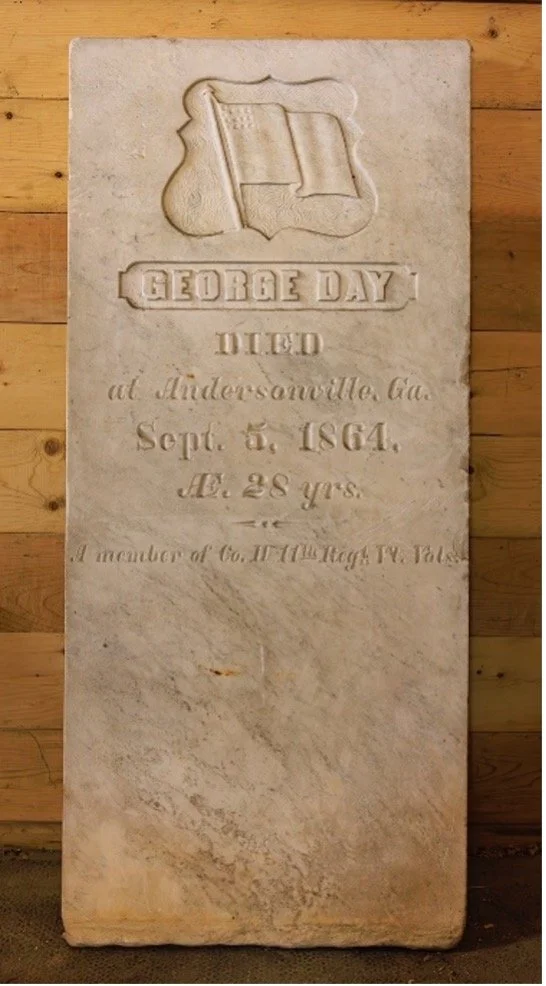

Continuing on this somber note: Below, a second cenotaph, one of white marble, commemorates George Day, a Union soldier from Strafford who was captured in the Civil War and sent to the infamous Confederate prison in Andersonville, Georgia. Of the 45,000 Union soldiers interned there, nearly a third, 13,000 of them, died there. As had so many others, George Day would die from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure. He was buried near the prison, a very long way from his home.

This white marble Cenotaph commemorates George Day

‘George Day died at Andersonville, Georgia/Sept. 5, 1864/age 28 years/A member of Co(mpany) II 11th Regiment, Vermont Volunteers.’

A century and a half after the end of the Civil War, the white marble cenotaph honoring George Day reached South Strafford. This gravestone, originally placed in the Day family plot in the Evergreen Cemetery in South Strafford, was replaced later by a large family monument. It was apparently then sold to an antique dealer, stored and forgotten. Some years ago, the gravestone began an odyssey back to South Strafford and thanks to a series of concerned and history-minded individuals came eventually to the attention of Gen and Dan Gibson, who with the help of Silas Treadway, delivered it to the Brick Store where it was displayed in the breezeway until it could be transported by Scott Knorlein and Dave Kyner to the Kyner barn.